Le Marais in 1900

Le Marais in 1900

Why architect Le Corbusier wanted to demolish downtown Paris

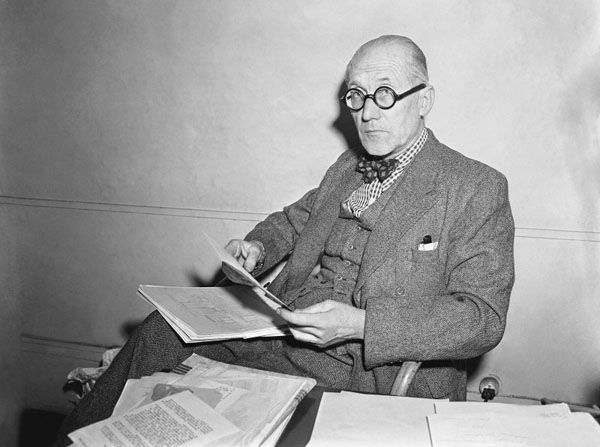

Walking through Le Corbusier's exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, I was surprised by how many of the great modernist architect's designs were never built. They were simply too radical, and none more so than his 1925 proposal to demolish two square miles of downtown Paris.

It's probably a good thing the architect, born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, didn't get his hands on Paris. The area he would have destroyed, including the 3rd and 4th arrondissements on the right bank of the Seine, is today among the prettiest, hippest, and most architecturally significant neighborhoods in the city. What's more, the replacement of organic urban areas with huge new developments has been criticized since the 1960s for sapping the vitality of cities.

All of that said, let's take a moment to appreciate how cool Le Corbusier's Plan Voisin would have been.

To start, demolishing central Paris made a lot of sense in the 1920s. The formerly aristocratic Marais district had fallen into squalor, characterized by poor sanitation, disease, and overcrowding, as chronicled by Marybeth Shaw in "Promoting An Urban Vision: Le Corbusier and the Plan Voisin." By 1921 in the Beaubourg area, 250 out of 276 houses were marked uninhabitable due to tuberculosis contamination.

Le Corbusier wanted to replace this urban blight with something incredible.

Plan Voisin called for 18 cruciform glass office towers, placed on a rectangular grid in an enormous park-like green space, with triple-tiered pedestrian malls with stepped terraces placed intermittently between them. Extending perpendicularly to the west, there would be an adjacent rectangle of low-rise residential, governmental, and cultural buildings amid more green space.

The new development would be integrated with highways, train and subway lines, as well as an airport, making this area the first thing that most visitors to the city would see.

The design sounds beautiful, as described by the architect :

I shall ask my readers to imagine they are walking in this new city, and have begun to acclimatize themselves to its untraditional advantages. You are under the shade of trees, vast lawns spread all round you. The air is clear and pure; there is hardly any noise. What, you cannot see where the buildings are ? Look through the charmingly diapered arabesques of branches out into the sky towards those widely-spaced crystal towers which soar higher than any pinnacle on earth. These translucent prisms that seem to float in the air without anchorage to the ground - flashing in summer sunshine, softly gleaming under grey winter skies, magically glittering at nightfall - are huge blocks of offices. Beneath each is an underground station (which gives the measure of the interval between them). Since this City has three or four times the density of our existing cities, the distances to be transversed in it (as also the resultant fatigue) are three or four times less. For only 5-10 per cent of the surface area of its business centre is built over. That is why you find yourselves walking among spacious parks remote from the busy hum of the autostrada.

The new office district would be the business center of the city, the country, and the world — while looking nothing like the "appalling nightmare" downtown streets of New York City. The adjacent housing district would be home to the world's business elite.

"Paris of tomorrow could be magnificently equal to the march of events that is day by day bringing us ever nearer to the dawn of a new social contract," Le Corbusier wrote.

To pay for the project, Le Corbusier counted on investment from France's business elite, promising a five-fold increase in land value. As for the denizens of the area that he wanted to destroy, the architect said these "troglodytes" could be relocated to garden cities in outer Paris.

As for concerns with leveling such a historic neighborhood, Le Corbusier insisted that the best architecture from the district — including the Palais Royal, the Place des Vosges, and certain townhouses and churches — would be saved. They would be, as described by Shaw, "preserved like museum pieces in the green carpet of the skyscrapers and low-rises that one would come upon while walking the curved paths of the parks."

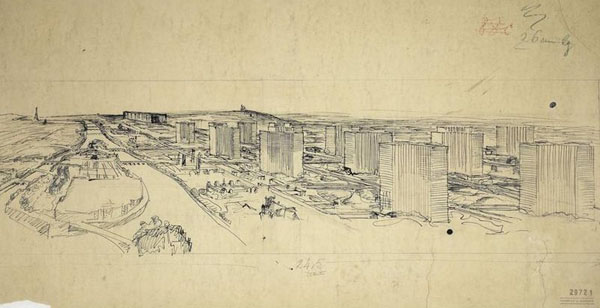

Now, courtesy of Fondation Le Corbusier, here's a sketch of the verdant business district:

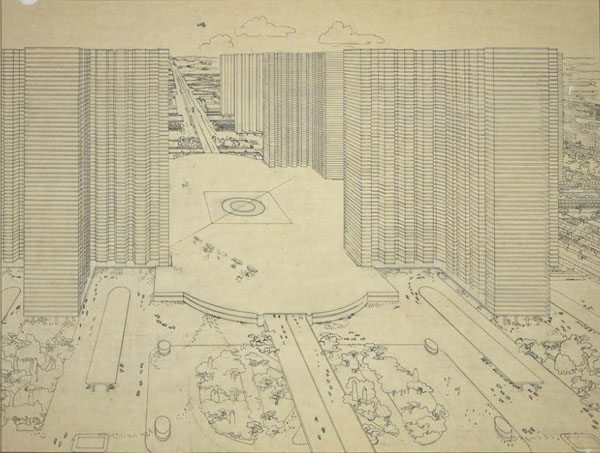

Here's a close-up showing the green spaces between buildings, with hints of ground-level commerce and transportation access:

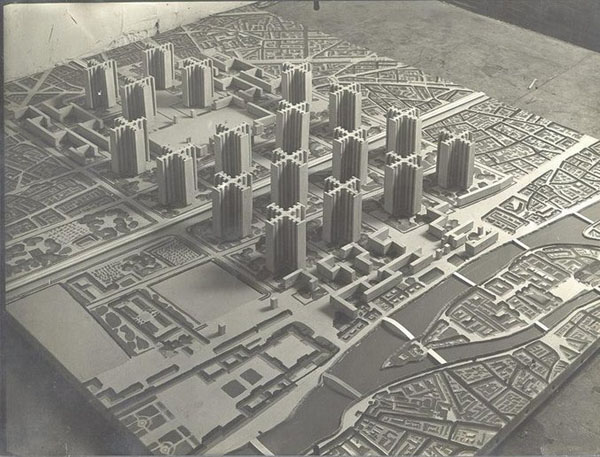

Here's a model showing the business district and part of the residential, cultural, and governmental district extending west along the Seine:

And here's what the area looks like today:

Fondation Le Corbusier has more images of the Plan Voisin.

A history of the Marais in the 1900's through postcards.

The Marais emerged as a district in the 14th century. The installation of Charles V at the Hôtel St-Pol rather than at the Palais de la Cité led to the enlargement of the city's eastern fortifications and the inclusion of the surrounding marshlands. The new royal sector quickly attracted the great lords and merchants and filled with luxurious hotels. This urbanization continued for three centuries until it reached its peak under Henry IV with the construction of the Place Royale, now Place des Vosges. In the 18th century, the upper middle class moved west to be closer to Versailles. It then gave way to craftsmen and provincials. After the Revolution, the convents and large residences became national property and were destroyed or divided up for profitability. The industrial revolution completes the transformation of the district which sinks little by little into insalubrity...

.jpg)

It wasn't until the 1930s that a reflection on the future of the Marais began. The modernists, who advocated the eradication of buildings and the construction of towers, were opposed to the Giovannoni school, which favored renovation. It is this last idea that will be imposed with the Malraux law of 1962 on the protection of urban ensembles and then with the Plan de sauvegarde et de mise en valeur (PSMV) adopted in 1996. Since then, the district has been able to rise from its ashes and regain the charm and activity it is known for.

The PARIMAGINE publishing house has created a collection "Mémoires des rues", encouraging Parisians and all lovers of the City of Light to get to know the different districts and their atmosphere better. You are invited to discover the city from a different perspective. These photos will help you discover the cultural heritage of Paris. The collection Mémoires des rues from Editions PARIMAGINE presents texts and photographs of the 3rd and 4th arrondissements at the turn of the 20th century.

The 3rd Arrondissement At The Turn Of The Century :

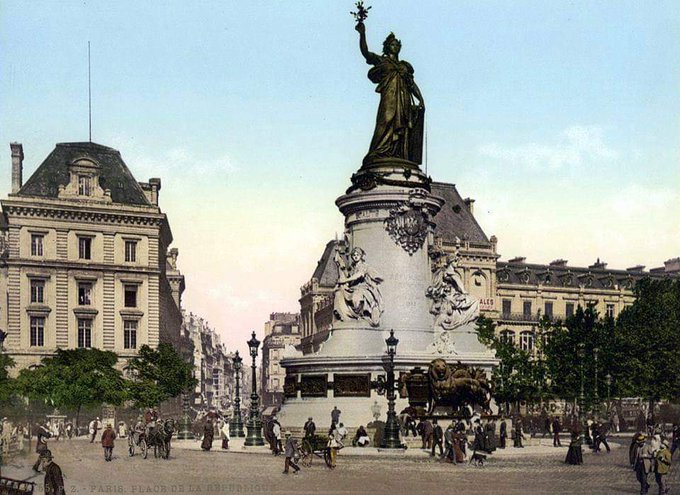

When flicking through the book on the 3rd arrondissement you will have an imaginary stroll around the north side of Le Marais, the Grands Boulevards, the market of the Carreau du Temple, where you will see a lot of second-hand clothes dealers, and the market of the Enfants Rouges, the oldest market place in Paris. You’ll imagine yourself dancing to the accordion of the “bals musette” rue au Maire, rue des Vertus or in the Strasbourg-Saint-Denis area or coming across a big square, the place de la République, the cour de Rome, the church of Sainte-Elisabeth and the synagogue of the rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth, the passage Molière and the passage of the Pont-aux-Biches, the beautiful mansions of the Marais, the oldest Parisian house, the stairs maker of the rue Montmorency, the hosiery shops of the rue Saint-Martin and the painting sellers of the boulevard “Sebasto”, the girls from the rue Quincampoix, the dressmakers of the rue du Temple; the coal sellers and the cafés of the rue Meslay: 250 photographs and as many surprises !

When flicking through the book on the 3rd arrondissement you will have an imaginary stroll around the north side of Le Marais, the Grands Boulevards, the market of the Carreau du Temple, where you will see a lot of second-hand clothes dealers, and the market of the Enfants Rouges, the oldest market place in Paris. You’ll imagine yourself dancing to the accordion of the “bals musette” rue au Maire, rue des Vertus or in the Strasbourg-Saint-Denis area or coming across a big square, the place de la République, the cour de Rome, the church of Sainte-Elisabeth and the synagogue of the rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth, the passage Molière and the passage of the Pont-aux-Biches, the beautiful mansions of the Marais, the oldest Parisian house, the stairs maker of the rue Montmorency, the hosiery shops of the rue Saint-Martin and the painting sellers of the boulevard “Sebasto”, the girls from the rue Quincampoix, the dressmakers of the rue du Temple; the coal sellers and the cafés of the rue Meslay: 250 photographs and as many surprises !The 4th Arrondissement At The Turn Of The Century :

With the book on the 4th arrondissement, you will travel from the secluded quarter of Notre-Dame to that of Saint-Merri or from the smart district of l’Arsenal to the working-class area of Saint-Gervais. You will go back a hundred years when flicking through this book. You will discover the private mansions of Le Marais, the maze of narrow streets that existed before the Centre George Pompidou was built, the nurses of the place des Vosges, the fruit and vegetable peddlers of the rue Saint-Antoine, the fishermen of the quai des Célestins, the bird market of the quai aux Fleurs, the astronaut of the place de la Bastille and the clothes sellers of the rue Simon-Le-Franc. You will get a view of old cafés, such as Au Canon de la Bastille or the Bar du Roi de Sicile and of old cinemas, such as the Cinéma Saint-Paul or the Cinéphone Saint-Antoine. You will also discover the Jewish quarter, the Pletzl, and the rue des Rosiers with its beautiful shop signs and its inhabitants, who held endless conversations in Hebrew: 250 photographs and as many surprises !

With the book on the 4th arrondissement, you will travel from the secluded quarter of Notre-Dame to that of Saint-Merri or from the smart district of l’Arsenal to the working-class area of Saint-Gervais. You will go back a hundred years when flicking through this book. You will discover the private mansions of Le Marais, the maze of narrow streets that existed before the Centre George Pompidou was built, the nurses of the place des Vosges, the fruit and vegetable peddlers of the rue Saint-Antoine, the fishermen of the quai des Célestins, the bird market of the quai aux Fleurs, the astronaut of the place de la Bastille and the clothes sellers of the rue Simon-Le-Franc. You will get a view of old cafés, such as Au Canon de la Bastille or the Bar du Roi de Sicile and of old cinemas, such as the Cinéma Saint-Paul or the Cinéphone Saint-Antoine. You will also discover the Jewish quarter, the Pletzl, and the rue des Rosiers with its beautiful shop signs and its inhabitants, who held endless conversations in Hebrew: 250 photographs and as many surprises !

.jpg)