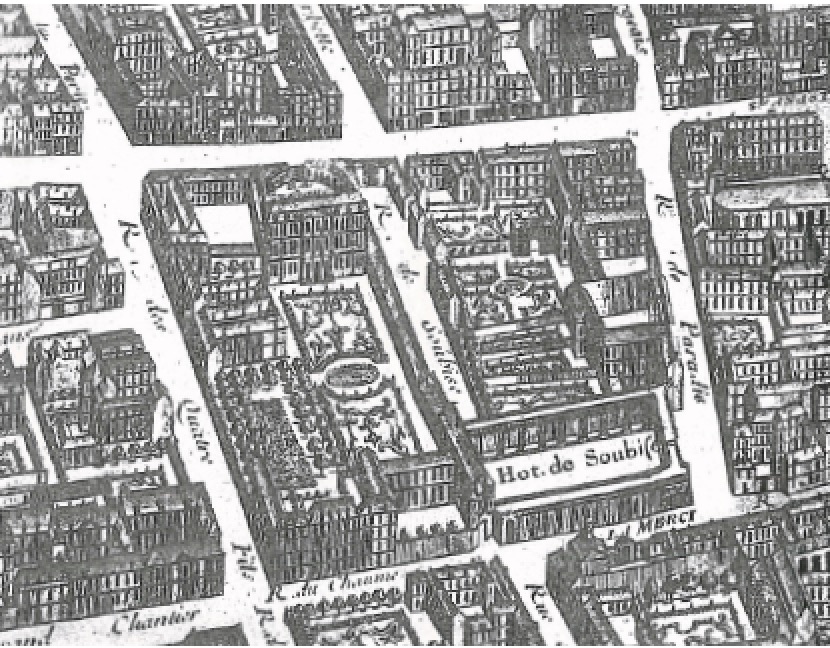

Le Marais in 1700

Le Marais in 1700

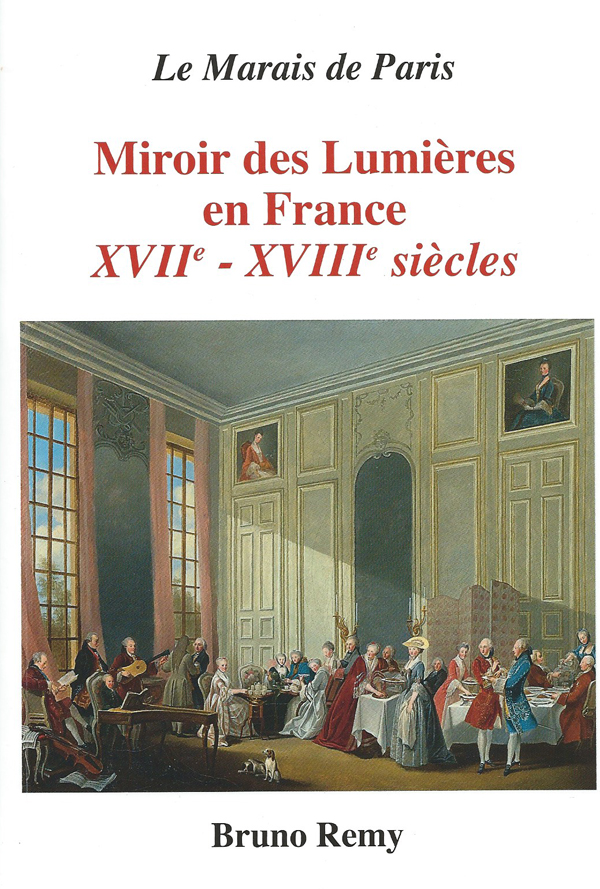

The Marais of Paris, Mirror of the Enlightenment in France - XVII-XVIII centuries

The Age of Enlightenment in France evokes the long struggle that opposed the freethinkers, later called philosophers, to the Church and the Monarchy which based its legitimacy on the divine right of kings.

That debate was not new, as the search for the truth to unravel the mystery of our planet originated with Socrates, Plato and Aristotle who used reason and not the intervention of some divinity to explain natural phenomena: Greek and Roman gods, although profusely venerated, often with grandeur, did not interfere in human affairs. That changed after the collapse of the Roman Empire and the emergence of Obscurantism characterized by God’s meddling in human affairs, and superstition in general.

The struggle between the freethinkers and the Obscurantists (denoting the enemies of the Enlightenment) encompassed two centuries. It started after the bloody wars of religion of the XVIe century, during the Counter-Reformation which saw the Jesuits trying to reestablish catholic faith in an all-out counter-offensive against the Protestants and the freethinkers. It coincided also with the individual starting to assert himself forcefully, like much earlier during the Renaissance in Italy, by adding his own input to the knowledge of Antiquity and to any of the new fields of activity that emerged during the Age of Enlightenment. .

This book, Le Marais de Paris, Miroir des Lumières en France, XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles, is devoted to the French Enlightenment as reflected through the history of the Marais, which is remarkably close to that of France, and takes into account the English influence in the field of politics and the sensitivity current which greatly changed people’s mentality.

It depicts two extraordinary centuries which saw endless philosophical battles fought against the evil of Obscurantism, still today a scourge of society in much of the world. Included in the description of the French Enlightenment are the Counter-Reformation, the Golden Age of the Marais, the Great Century or the Age of Louis XIV, a period of utmost absolutism, and the Century of Enlightenment.

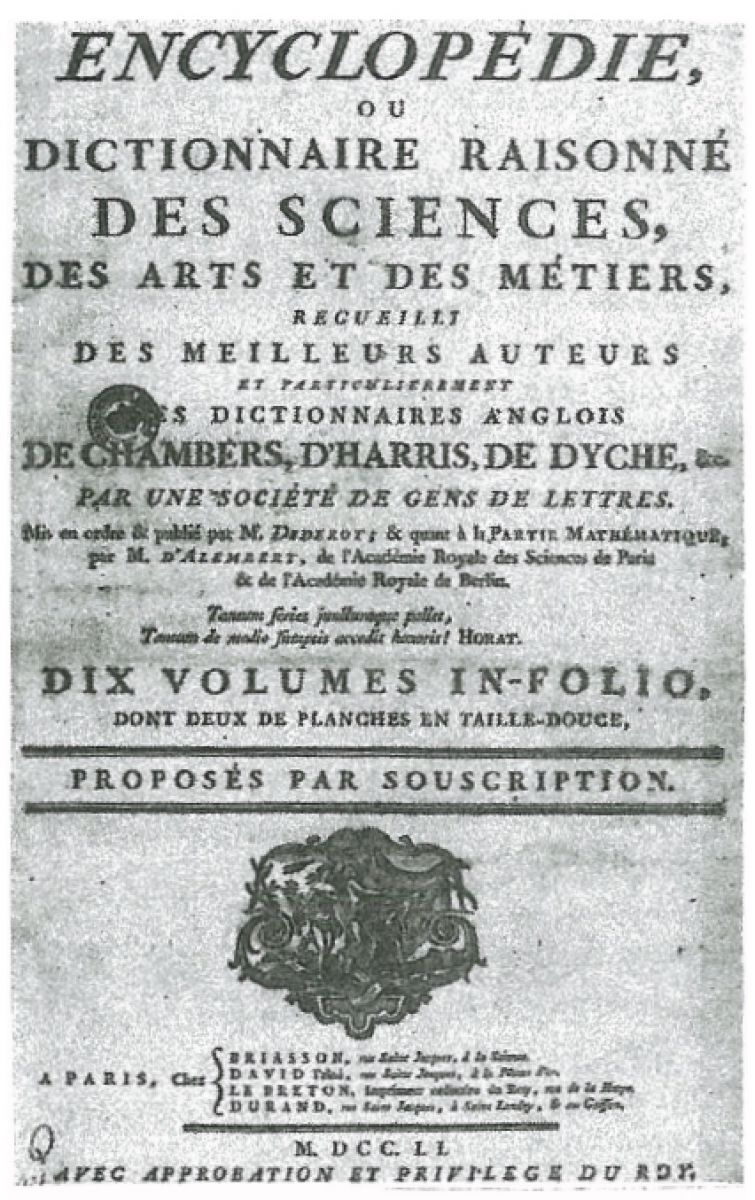

Starting, as it is generally accepted with Newton (1642-1727), the siècle des Lumières, which saw the triumph of the sciences regrouped in the Diderot Encyclopedia, was meant to bring happiness on earth to men who thought they had attained it after the storming of the Bastille on the 14th of July 1789, but sank into total disillusion after the September 1792 Massacre which started the Reign of Terror (1792-94).

This book draws the portraits of numerous persons who played an active role in the development of human rights in France but also of those who supported fully the Ancien Régime. Also remembered are the freethinkers and all other members of society who, like the illustrious Fouquet, fell victims to injustice and intolerance till the French Revolution.

These people lived often side by side, sometimes in the same street, in a complex society where reigned injustice, religious intolerance, censorship, poverty and above all inequality. That was not altogether the case in other parts of Europe which were torn apart by intolerance and were ruled by enlightened kings who undertook extensive reforms, like ending slavery and granting freedom of expression. In France, Louis XV and Louis XVI were sincere in their quest for reforming society but ceded under the pressure of the privileged classes unlike Frederick II in Prussia, Gustavus III in Sweden or Joseph II, brother of Marie Antoinette, in Austria.

Shown below are some of the people who, by their actions, hampered or contributed to the development of the Enlightenment in France, and a number of churches and grandiose mansions (hôtels particuliers) dating from that flourishing period in French history.

Some of the strongest defenders of the Ancien Regime were the Kings’ confessors and preachers, amongst them:

Père Coton, Henry IV’s confessor convinced the king to let the Jesuits return to France. They had been expulsed from that country after they were implicated in his attempted assassination. Had they not returned to France, there would have been fewer colleges to educate the elite of society which would have given less impulse, through the teaching of humanities, to the development of the Enlightenment.

Père Caussin, Louis XIII’s confessor, persuaded the king to revert the French alliance with the Protestants during the Thirty Years’ War. He was thwarted by Cardinal Richelieu who retained the confidence of the feckless king. Had that not been the case, there probably would not have been any Peace of Westphalia (1648) which resulted in religious tolerance in the Holy Roman Empire.

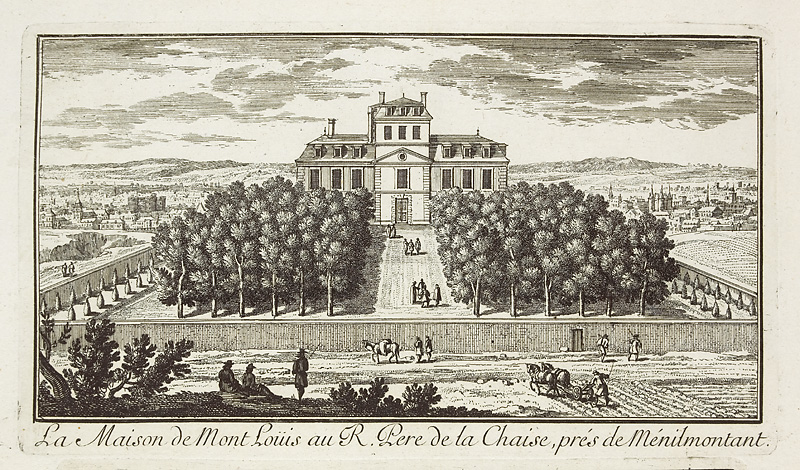

Père La Chaise, Louis XIV’s confessor may have had a say in separating Madame de Montespan from the king after the Affair of Poisons (affaire des Poisons). He may have also secretly married Madame de Maintenon to Louis XIV. More important, he may have prevented, according to some historians, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, although Voltaire did not share that view. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which delighted Madame de Sévigné, caused considerable damage to the French economy. Le Père La Chaise is mostly remembered today for the cemetery of Père La Chaise where he had a summer house in Mont Louis.

Preachers like Bossuet and Bourdaloue, whose task was to remind the faithful of their Christian duties. were most effective in making libertine aristocrats come back to the fold of the Church. In 1687, in the funeral sermon for the Grand Condé, Bourdaloue praised the great warrior for his military exploits, but omitted any reference to his philandering and cruelties like locking away his wife in the countryside at Châteauroux.

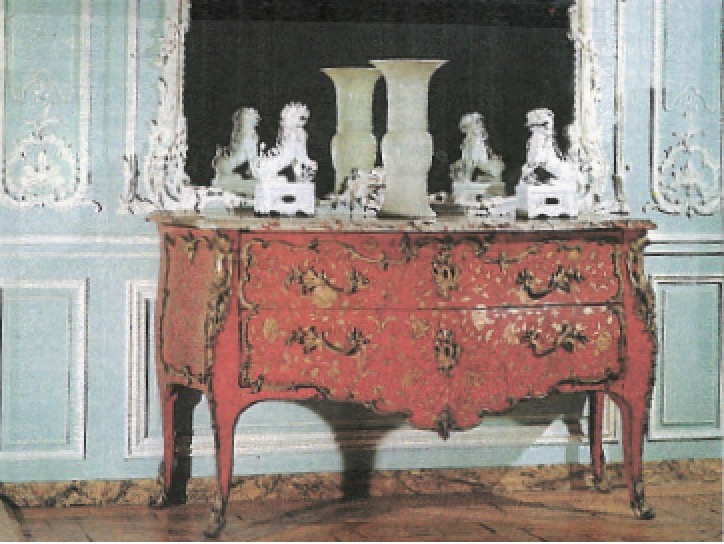

King’s official mistresses were also influential in nominating ministers, except in the case of Louis XIV who ruled by himself (“L’État, c’est moi”). Louis XV, on the contrary, let himself be influenced by Madame de Pompadour. She convinced him to dismiss able ministers who had offended her (she was a commoner) but were trying to reform the monarchy. It was thanks to her, however, that the rococo style flourished in France and Europe as the king was mostly interested in sciences, and that Diderot’s Encyclopedia continued to be published.

Other figures of the Enlightenment range from poets, other writers and artists to courtesans, scientists and philosophers.

Théophile de Viau stood for poetic “invention” and refused to be bound by the classical rules imposed upon poetry by Malherbe. He was dismissed by the classics and not rediscovered until the pre-romantic period. His espousing Epicureanism put him to a lot of trouble – he was condemned to be burned at the stake but managed to hide in the Marais – , and died at the age of 39 after enduring two years of harsh imprisonment at the Conciergerie.

The courtesan Ninon de Lenclos, remembered for her amour galant, stood for women’s rights like other “précieuses”, namely Mademoiselle de Scudéry and also Madame de Sévigné who preferred to remain single (Madame de Sévigné after the death of her young husband in a duel) rather than falling into the grips of men who often exercised tyrannical authority over their wives and children. Chattel marriages were usually the norms in aristocratic circles. The marquise de Sévigné, whose main worry was to tend to her married daughter, remained all her life a staunch supporter of the monarchy and the Church. Also remembered is Théroigne de Méricourt who, at the Convention, dared criticize men who were in their majority misogynists and who thought the place of women in society is at home (au foyer), was severely beaten by bellicose women called tricoteuses (knitters) who sat in the assembly. She died in 1817 after spending 23 years (half her life) at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris.

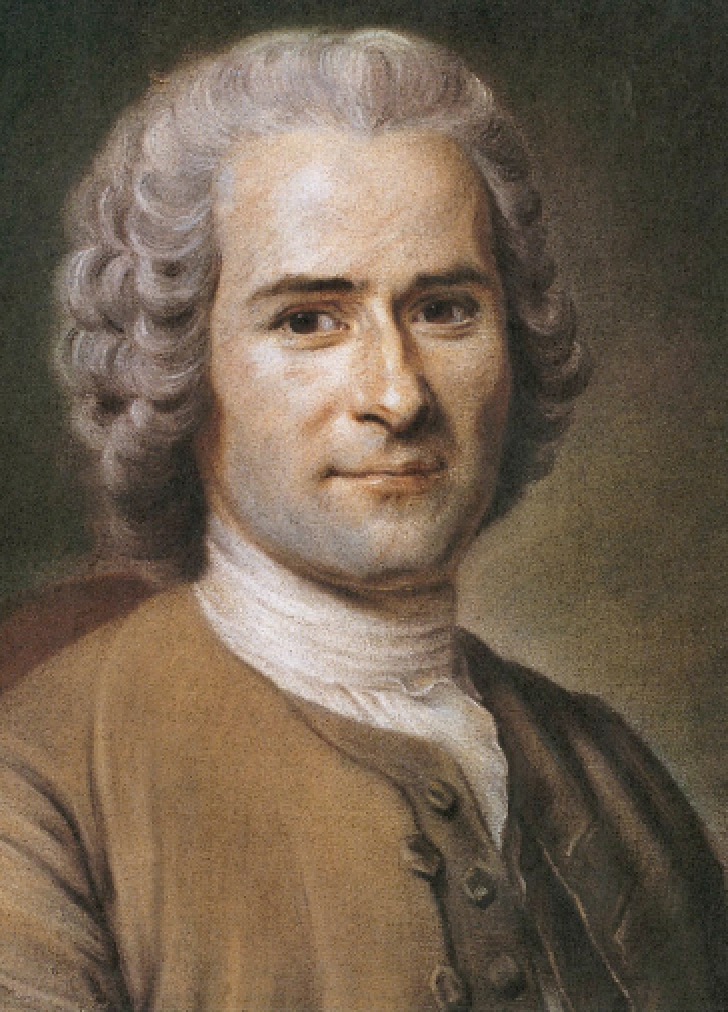

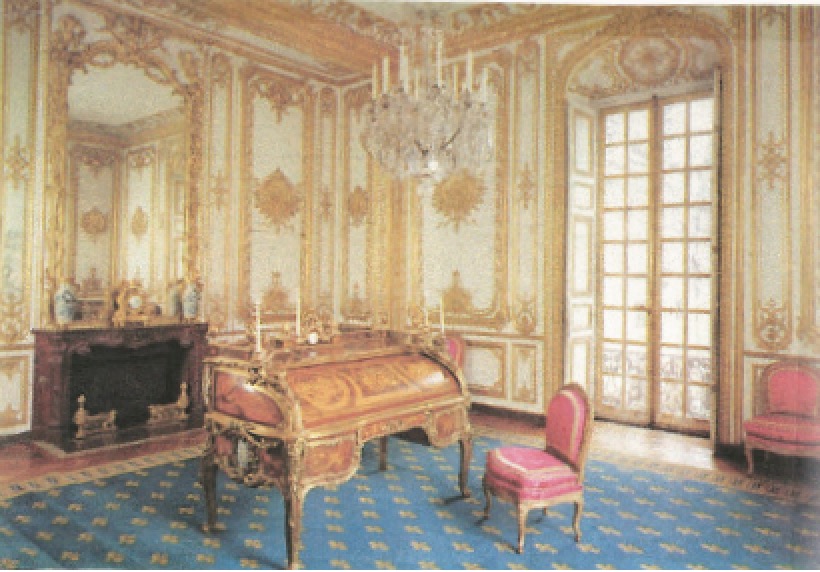

Scientists like Père Mersenne, Pascal and Lavoisier, philosophers like Descartes, Rousseau and Voltaire, writers like Corneille, Pascal, Beaumarchais, contributed a lot to the development of the Enlightenment. Mlle de Scudéry, a précieuse, and Scarron, a burlesque poet, greatly enriched the French language which became the language of the Enlightenment (langue des Lumières) enabling European intellectuals to communicate with each other through the informal republic of letters. Great architects, like Pierre-François Delamaire, François and Jules Hardouin Mansart, and painters, also left their marks in the Marais as attested by the existence in that beautiful quarter of Paris of many fully restored hôtels particuliers like the hôtel de Soubise, hôtel de Rohan and the hôtel de Sully, but only a few religious buildings on account of the wanton destruction of countless religious structures during the Revolution, like the church of La Visitation Sainte Marie with its remarkable rotunda and the baroque church of Saint-Paul Saint-Louis.

This richly illustrated book which, with the first book on the Middle Ages, Le Vieux Paris, La fondation et l’évolution du Marais médiéval, completes the whole history of the Marais, is replete with themes that gave rise to the universal principles that are enshrined in the French Constitution and the Charter of the United Nations, is available in the Marais at the Association pour la Sauvegarde du Paris historique, 44-46, rue François Miron, and the Librairie de l’Hôtel de Sully, 62, rue de Rivoli, 75001, and outside Le Marais district, at the Librairie Galignani, 224, rue de Rivoli, 75001 Paris, where the book can be ordered at tél. 01-42 607 607 and fax 01-42 860 931, and outside of Paris It can also be bought chez l’auteur, maraishistorique-paris.eu

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)